The twins

Nearly eighteen years ago, Marcia Margolin, a fellow Feldenkrais® teacher here in Santa Cruz, asked me if I’d be interested in seeing two identical twin infant boys. She didn’t work with children and knew that I did.

The boys were born prematurely and, at six months old, had no self-generated movement. Neither of them could grasp, reach, feed themselves, or roll from one side to another. One of the boys had little muscle tone, kind of like Raggedy Andy, and the other had so much that he was like the Tin Man.

The twins had yet to take to or benefit from any of the physical therapies and hands-on work they’d been exposed to up until then. They were shy and reluctant to be touched. During our first hands-on session, I took time to get to know them, accompanying and facilitating the small movements they made when they shifted weight, no matter how minimally, or turned their heads to look at each other, their parents, and, occasionally, me. I used my hands to listen and to ask them to listen to themselves. I had no agenda, no learning outcome in mind. My only aim was to connect, to recognize their interests and intentions as expressed through their actions, sounds, and breathing, and to begin to explore — slowly, carefully, only within the range that was easy and comfortable for them — what they were already capable of doing. It wasn’t until years later that Phoenix, their mom, told me that they each rolled over for the first time ever after that initial Functional Integration® lesson.

Wanting to document these sessions, almost immediately after we started working together, I asked for and received permission to video the lessons. However, it soon became clear that the time the twins were most comfortable being touched was when then they were nursing. I would work with each one of them as long they were interested and engaged, sometimes switching back and forth a few times during one lesson. Though their mom was fine with us filming these lessons, not knowing who would be watching at some later date or how they’d see it, it just felt too weird and creepy to me, so I decided against it.

From when they were around six months old until they were 5½ years old, I worked with Bodhi and River regularly, well as regularly as was possible between my frequent trips to teach in Feldenkrais teacher trainings and post-graduate programs around the world. That meant I’d see them once, sometimes twice a week, for a few weeks in a row, and then not see them again for several weeks or more.

It was fascinating to see how well this intermittent schedule of (infrequent) sessions worked for the twins’ learning. At each step along the developmental pathway — for each of them individually and both together — I attended to what they were curious about, tracking what engaged them, and figuring out how to make what they were already doing easier.

True to Moshe’s method, instead of trying to teach them to do new things, we explored new ways of doing the things they could already do. Proceeding slowly to the early stages of motor development, they became better at moving around themselves and then, gradually, to move themselves around more easily and in more and more varied ways. In this way, they learned different ways to roll over, wiggle around, and, eventually, to crawl on their bellies. Each of them progressed in his own way and at his own time and, tethered together as only twins can be, they also moved forward collectively, bouncing off each other’s progress and learning together. Months later, they each found their own way to creep on their hands and feet and, years later, to walk, skip, jump, and run.

(Once the boys started to move, it became clear that they weren’t just simply shy, which led to the diagnosis of autism. Their dad, Ocean, writes about this aspect of their lives here.)

The boys lived in a loving multigenerational household, had wonderful caretakers, and, through their parents’ work, were embedded in a lively community of environmental activists from around the world. All their needs were being responded to by all those attentive and caring adults around them. As wonderful as this was, at one point I realized that this was actually an impediment to their progress. If all they needed to do was to look at or point to something they wanted and express their desire through the sounds they made, they would never be motivated to move on their own. I had a confab with the family to discuss this and to come up with ways to inspire them to realize their intentions through their own actions. For instance, instead of giving them a snack directly, we decided to place it within reach so that they were given a chance to move towards it before it was given to them. For another example, instead of putting their shoes on in one action, their foot was first put partway in the shoe to give them a chance to slide their foot in on their own.

Though they didn’t speak, the boys revealed their emotions and desires through the expressive sounds they made. Like so many twins, they also shared an unspoken bond and a secret language all their own. Their passive understanding of language grew more sophisticated and nuanced. However, when the boys were around 4½ years old, I started to be concerned that they weren’t speaking and appeared to have no interest in doing so. From what I’d learned in my graduate studies, I was concerned that they might miss the critical window for developing language and that this could, in turn, severely limit their cognitive development.

When she was visiting from Atlanta, I asked speech therapist and Feldenkrais colleague, Marina Gilman, to meet with me and the boys’ parents to review their communication abilities and discuss the situation. Though the boys were, by then, well on their way to developing the physical and neuromuscular ability to speak, nothing had inspired them to start doing so. Having just read Oliver Sack’s wonderful book, Seeing Voices, I knew that it didn’t matter what language the boys learned as long as they learned some language. Since the community their parents were involved in was committed to diversity, I suggested that they take it upon themselves to learn American Sign Language (ASL) so that the community could more easily reach out to and then be able to interact with the deaf. That way instead of the boys being put into situations that obliged them to learn to speak, they would be immersed in a social context where everyone was learning ASL.

This benevolently devious strategy worked. At one point the boys went from signing to speaking. Their progress from saying words to speaking sentences and paragraphs took weeks, not many months or years. When they spoke, they used ASL grammar, which is markedly different from English grammar and made for a unique and poetic mode of expression.

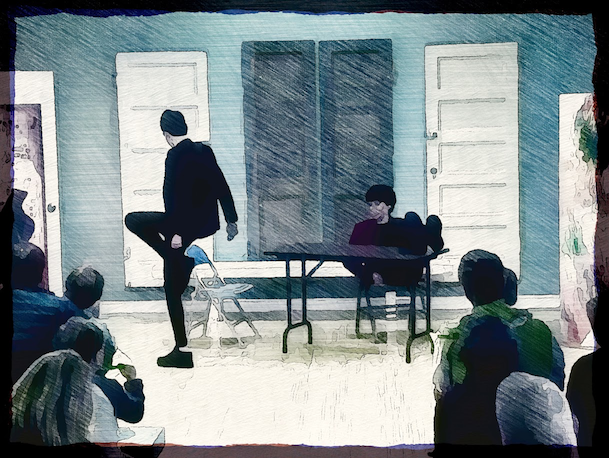

This was only the beginning of speaking out and engaging with the world. With thousands of hits on YouTube, the version of the Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream speech” that Bodhi and River recorded when they were 11 years old became a hit. When they were 15, they performed and recorded Monty Python skits including the classic Ministry of Silly Walks. Then, just in time for their 18th birthdays earlier this year, the boys published a collection of fables that they themselves created.

The boys’ progress is a testament to their ability to learn and to the way in which the Feldenkrais Method® of NeuroPhysical Learning (NPL) taps into that ability. It’s also a wonderful example of how rewarding and worthwhile this work is for all involved.

Your thoughts?

Please let us know your perspective! Add your comments, reactions, suggestions, ideas, etc., by first logging in to your Mind in Motion account and then clicking here.

Commenting is only available to the Mind in Motion Online community.

Join in by getting your free account, which gives you access to the e-book edition of Articulating Changes (Larry's now-classic Master's thesis), ATM® lessons, and more — all at no charge whatsoever.

To find out more and sign up, please click here.

Please share this blog post

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

This blog may contain one or more affiliate links. When you click on a link and then make a purchase, Mind in Motion receives a payment. Please note that we only link to products we believe in and services that we support. You can learn more about how affiliate links work and why we use them here

Responses